Principal Component Analysis Explained

What is PCA?

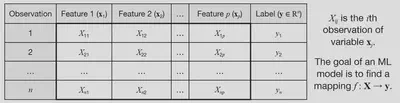

Given a set of features

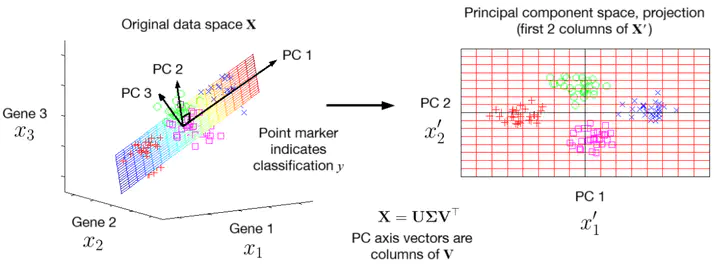

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a transformation of the original features into a set of new features that are uncorrelated, and ordered by the amount of variance they capture from the original data. Mathematically, it is a rotation of the coordinate axes used to specify the data into axes along which variance is maximised and covariance is minimised. This allows for dimensionality reduction by selecting only the first few principal components, which retain most of the information while reducing redundancy.

We can denote the new features returned by PCA (called principal components, PCs) as

If the original data matrix is

Standardised data

Before computing the PCs, we need to standardise the data, which is a simple shifting and scaling to ensure the dataset has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 in each feature. For column

where

The PCA transformation (using SVD)

Given our standardised data matrix

- Singular value decomposition (SVD) of the data matrix

- Eigendecomposition of the covariance matrix

We will use the SVD approach here, since it is more numerically stable and efficient for large datasets, and then show how it is equivalent to the covariance matrix method.

The SVD of any matrix

where

- The columns of

- The columns of

- The singular values in

Now to apply the PCA transformation, we just compute

Either formula gives the same result: the first one is a little easier to interpret, as it can be written like a transformation matrix acting on our data:

so

We can see that the formula for computing

where

The fact that the columns of

Covariance matrix

The covariance matrix

such that the covariance of features

The uncorrelatedness (independence) of the PCs can be seen by the fact that the covariance matrix of

which can be rearranged to get

This also provides an alternative way to compute the PCA transformation: by first computing scikit-learn library), the SVD approach is used, since highly optimised algorithms exist for the efficient computation of a direct SVD.

Dimensionality reduction

Since the PCs are ordered by the amount of variance they capture from the original data, we can reduce the dimensionality of the data by selecting only the first

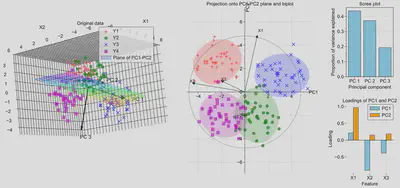

We can illustrate this with an example. A dataset in three features

Notice that the clusters remain well-separated in the reduced 2D space, indicating that most of the information in the original data is retained. This would allow algorithms such as regression, classification or clustering to perform well with a lower dataset size, giving faster performance. The arrows in the first figure show the directions of the three PCs in the original feature space.

The second figure shows the directions of each original feature in the PC space. When superimposed on the PCs, this is called a biplot. On the right of the figure, the scree plot shows the proportion of variance explained by each PC, which are the relative size of the eigenvalues of

Python code to generate the figure above (on GitHub Gists here):

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.gridspec as gridspec

import matplotlib_inline

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

#plt.style.use(r'C:\LibsAndApps\Python config files\proplot_style.mplstyle')

matplotlib_inline.backend_inline.set_matplotlib_formats('svg')

# input settings

means = np.array([[2, 2, 2], [-2, -2, 1], [2, -2, -2], [-2, 2, -1]])

n_points = 40

spread = 1.0

colors = ['r', 'g', 'b', 'm']

label_names = ['Y1', 'Y2', 'Y3', 'Y4']

markers = ['+', 'o', 'x', 's']

arrow_scale = 5

feature_names = ['X1', 'X2', 'X3']

# generate data with clusters

data = np.array([mean + spread * np.random.randn(n_points, 3) for mean in means])

X = np.vstack(data)

# transform into PC coordinates

pca = PCA(n_components=3)

X_pca = pca.fit_transform(X) # this is X' in the text above

#### Figure ####

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(17, 7))

fig.subplots_adjust(wspace=0.7, hspace=0.4)

grid = gridspec.GridSpec(2, 5)

#### First subplot: points in 3D space with plane spanning PC1 and PC2 (where PC3 = 0)

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(grid[0:2, 0:2], projection='3d')

# data points

for i, (cluster, color, marker) in enumerate(zip(data, colors, markers)):

ax1.scatter(cluster[:, 0], cluster[:, 1], cluster[:, 2],

c=color, marker=marker, s=50, alpha=0.7, label=label_names[i])

# plane PC3 = 0

pc1, pc2, pc3 = pca.components_

mean = pca.mean_

u_min = int(np.floor(min(X_pca[:, 0])))

u_max = int(np.ceil(max(X_pca[:, 0])))

v_min = int(np.floor(min(X_pca[:, 1])))

v_max = int(np.ceil(max(X_pca[:, 1])))

u = np.linspace(u_min, u_max, u_max - u_min + 1)

v = np.linspace(v_min, v_max, v_max - v_min + 1)

U, V = np.meshgrid(u, v)

plane_points = mean + U[:, :, np.newaxis] * pc1 + V[:, :, np.newaxis] * pc2

X_plane, Y_plane, Z_plane = plane_points[:, :, 0], plane_points[:, :, 1], plane_points[:, :, 2]

ax1.plot_surface(X_plane, Y_plane, Z_plane,

facecolors=plt.cm.gist_rainbow((Z_plane - Z_plane.min()) / (Z_plane.max() - Z_plane.min())),

alpha=0.2, rstride=1, cstride=1, label='Plane of PC1-PC2')

# arrows for PC axes

for i, pc in enumerate(pca.components_):

ax1.quiver(mean[0], mean[1], mean[2],

pc[0]*arrow_scale, pc[1]*arrow_scale, pc[2]*arrow_scale,

color='k', linewidth=2, arrow_length_ratio=0.1)

ax1.text(mean[0] + pc[0]*arrow_scale*1.2, mean[1] + pc[1]*arrow_scale*1.2, mean[2] + pc[2]*arrow_scale*1.2,

f'PC {i+1}', color='k', fontsize=12)

ax1.set_box_aspect(None, zoom=1.3)

ax1.set_xlabel('X1')

ax1.set_ylabel('X2')

ax1.set_zlabel('X3')

ax1.set_title('Original data')

ax1.legend()

#### Second subplot: projection onto PC1 and PC2

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(grid[0:2, 2:4])

for i, color, marker in zip(range(means.shape[0]), colors, markers):

# data points

X_pca_i = X_pca[n_points * i : n_points * (i + 1), :]

ax2.scatter(X_pca_i[:, 0], X_pca_i[:, 1], c=color, marker=marker, s=50, alpha=0.7, label=colors[i])

# confidence ellipses for clusters

cov = np.cov(X_pca_i.T)

sigma = 2 # 2 sigma = 95% confidence interval

lambda_, v = np.linalg.eig(cov) # eigenvalues and eigenvectors of covariance matrix

lambda_ = np.sqrt(lambda_) # square root of eigenvalues

ell = plt.matplotlib.patches.Ellipse(

xy=np.mean(X_pca_i, axis=0),

width=lambda_[0] * sigma * 2, height=lambda_[1] * sigma * 2,

angle=np.rad2deg(np.arccos(v[0, 0])), facecolor=colors[i], alpha=0.2)

ax2.add_artist(ell)

circle_scale = min([abs(x) for x in [*ax2.get_xlim(), *ax2.get_ylim()]])

for (feature_name, pc1, pc2) in zip(feature_names, pca.components_[0], pca.components_[1]):

ax2.arrow(0, 0, pc1 * circle_scale, pc2 * circle_scale, head_width=0.2, head_length=0.2, fc='k', ec='k')

ax2.text(pc1 * circle_scale * 1.1, pc2 * circle_scale * 1.1, feature_name, fontsize=10)

circle = plt.Circle((0, 0), circle_scale, color='black', alpha=0.5, fill=False)

ax2.add_artist(circle)

ax2.set_xlabel(f'PC2 ({pca.explained_variance_ratio_[0]:.2%})')

ax2.set_ylabel(f'PC2 ({pca.explained_variance_ratio_[1]:.2%})')

ax2.set_xlabel("PC1")

ax2.set_ylabel("PC2")

ax2.set_title('Projection onto PC1-PC2 plane and biplot')

ax2.axis('equal')

ax2.xaxis.set_label_coords(1, 0.5)

ax2.yaxis.set_label_coords(0.5, 1)

ax2.spines['bottom'].set_position(("data", 0))

ax2.spines['left'].set_position(("data", 0))

ax2.spines['top'].set_visible(False)

ax2.spines['right'].set_visible(False)

#### Third subplot: Scree plot

ax3 = fig.add_subplot(grid[0, 4])

ax3.bar(['PC 1', 'PC 2', 'PC 3'], pca.explained_variance_ratio_, color='skyblue', edgecolor='black')

ax3.set_xlabel('Principal component')

ax3.set_ylabel('Proportion of variance explained')

ax3.set_title('Scree plot')

#### Fourth subplot: Loadings

ax4 = fig.add_subplot(grid[1, 4])

ax4.bar([i - 0.15 for i in range(1, len(pca.components_[0]) + 1)], pca.components_[0],

color='skyblue', width=0.3, edgecolor='black', label='PC1')

ax4.bar([i + 0.15 for i in range(1, len(pca.components_[1]) + 1)], pca.components_[1],

color='orange', width=0.3, edgecolor='black', label='PC2')

ax4.set_xlabel('Feature')

ax4.set_ylabel('Loading')

ax4.set_xticks(range(1, len(pca.components_[0]) + 1))

ax4.spines['top'].set_visible(False)

ax4.spines['right'].set_visible(False)

ax4.spines['left'].set_visible(False)

ax4.spines['bottom'].set_visible(False)

ax4.axhline(0, color='black', linewidth=0.8)

ax4.set_xticklabels(feature_names, rotation=0)

ax4.minorticks_off()

ax4.legend()

ax4.set_title('Loadings of PC1 and PC2')

plt.savefig('Figure.svg')

plt.show()