Evidence for Evolution

A collection of pictures, papers and examples that support the theory of evolution.

A collection of interesting pictures, papers and examples to show how biological evolution explains the diversity of life.

CONTENTS

- Direct Observation

- Genetics

- Molecular Biology

- Paleontology and Bioanthropology

- Geology

- Biogeography

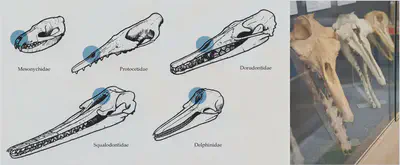

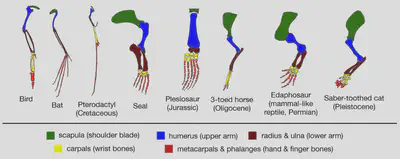

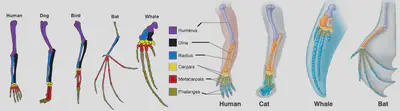

- Comparative Anatomy

- Comparative Physiology

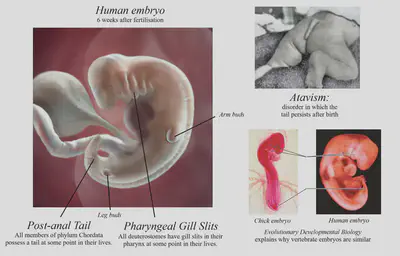

- Developmental Biology

- Population Genetics

- Metagenomics

- Applications of Evolution

1. DIRECT OBSERVATION

Microevolution (adaptation and other changes within a species) is commonly observed, but the more striking consequences of evolution usually take place on timescales far too long to observe from start to finish. However, there are some well-established cases where macroevolution can be observed in real time. Some definitions here will be useful:

- Biological species concept ~ a species is any group who is reproductively isolated from other such groups, due to e.g. behavioural isolation, genetic incompatibility or failure to produce viable offspring. This is the most common species concept for studying extant life, but is undefined for asexual organisms (prokaryotes), so another concept is required.

- Phylogenetic species concept ~ a species is the smallest monophyletic grouping when performing comparative genomic analysis on a population. This is much more suited for prokaryotes, defining species via genetic similarity.

- Speciation ~ formation of more than one species from a population of one species, where species is defined suitably using one of the species concepts (like the above).

- Macroevolution ~ variations in heritable traits in populations with multiple species over time. Speciation marks the start of macroevolution.

Although microevolution is useful for conceptualising how Darwinian evolution works (e.g. adaptation: heritable changes with natural selection), it is somewhat trivial and is not contested by critics of evolutionary theory. Therefore, we will list here only examples of macroevolution that have been observed in real time. Most of these are in the wild, with a few lab-based studies included too.

If macroevolution can be observed, and we know of no means by which the mechanisms of neo-Darwinian evolution (mutation/selection/drift/gene flow) can stop, and we have consilient evidence indicating continuation of the process back through time, and there is no reason to believe any contrary explanations (e.g. intelligent design/creationism), then the methodologically naturalistic, parsimonious, evidence-driven conclusion follows.

Direct observations are not the best evidence of evolution as a whole. Direct observation is just one line of inquiry: the other lines serve to justify and corroborate the extrapolation of those observations through deep time, synthesising the theory of evolution as we know it.

Lizards evolving placentas

.](/post/evolution-evidence/lizard_viviparity_hu2301c354ee25b1ddf3c689865b476020_1508251_ffc86fff1a9b0c13b52cda7d8cbca2ab.webp)

Reptiles are known for usually giving birth via egg-laying (oviparity), but there is evidence that some snakes and lizards (order Squamata) transitioned to giving live birth (viviparity) independently and recently. A ’transitional form’ between these two modes is ’lecithotrophic viviparity’, where the egg and yolk is retained and held wholly within the mother.

While observing a population of the lizard Zootoca vivipara in the Alps, reproductive isolation was found between these two subgroups, and attempts at producing hybrids in the lab led to embryonic malformations. Sometimes, the viviparous group would even give birth to two live young and one egg within the same litter of three. The oviparous group is now confined to the range spanning northern Spain and southern France (the Pyrenees), while the viviparous lizards extend across most of Europe. This represents an example of speciation with complete reproductive isolation, together with the gain of a complex new function (viviparity) to boot.

Sources: here (paper), here (paper) and here (video).

Fruit flies feeding on apples

.](/post/evolution-evidence/apple_maggot_fly_hue8d28482ff591f37d49c69670e986388_909515_5a5c59ad9e1510a4778c5e8deecdef13.webp)

The apple maggot fly (Rhagoletis pomonella) usually feeds on the berries of hawthorn trees, and is named after apples only because eastern American/Canadian apple growers in 1864 found its maggots feeding on their trees. Since then, the apple-eating and berry-eating groups have become more distinct.

This is a case of ‘sympatric speciation’: the geographic range of the apple group (north-eastern America) is contained within that of the berry group (temperate biomes globally). There is a barrier between the groups because 1) the two trees flower at different times of the year (apples in summer, hawthorns in autumn/fall) so flies must reproduce asynchronously, and 2) each group only lays its eggs on their respective fruit.

Sources: here.

The London Underground mosquito

.](/post/evolution-evidence/london_underground_mosquito_hu2cf80dceaca8b5e6f047f5d87bbd7801_381541_47de307ab3f58ea606154ff1820e42ca.webp)

They were named due to people being bit by them while hiding in the underground tunnels of London’s tube train network during the Blitz of World War 2. It’s recently been shown that they did not first evolve there. It turns out that the ancestral species, Culex pipiens, lived above ground, while the new species, C. p. f. molestus, evolved in the Middle East ~2000 years ago, adapted to warm and dark below-ground city environments, of which the sealed tunnels of the 1860s London Underground was one.

The new species breeds all-year-round, is cold intolerant and bites rats, mice and humans, while the prior species hibernates in winter. This is a case of ‘allopatric speciation’ (geographic isolation) by ‘disruptive selection’, a rarer type of natural selection where an intermediate trait is selected against while extreme traits are favoured, leading to rapid separation into a bimodal distribution of the two lifecycles. Cross-breeding the two forms in the lab led to infertile eggs, implying reproductive isolation.

Multicellularity in Green Algae

.](/post/evolution-evidence/green_algae_multicellular_hu2476658086b3933203d9cc5a8424b5d3_286455_baf9eb50f803f8fcd9291f3b1b0018ce.webp)

‘Colonialism’ (simple clumping/aggregation of single-celled organisms) is well-known, and does not count as multicellularity. But if the cells become obligately multicellular (lifecycle uses clonal division by mitosis and remain together, and splitting them apart kills the organism), the groundwork for de novo multicellularity is laid. This was observed in the lab by introducing a population of green algae (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a protist) to cultures of another predatory protist, over a period of 1 year (~750 generations). The strong selective pressure to defend against predation led to obligate multicellularity in the algae. This process, featuring increasingly large clusters of cells, is well-reflected in the extant clade Archaeplastida, which includes green algae (single cell protist), a variety of other colonial protists and plants (complex multicellular).

Another common trait of extant multicellular life is differentiated tissue formation due to cell specialisation. This too has been observed, and represents the formation of complex genetic control systems (by negative feedback loops) as studied by evolutionary developmental biology. Volvox is a good example, being within clade Archaeplastida (above) and having two cell types - one for sexual reproduction, one for phototaxis. Genetics also finds that the famous ‘Yamanaka factors’ for cell differentiation (as well as many other key innovations like cell-to-cell signaling, adhesion and the innate immune system) in animals inherit from those in choanoflagellates (the closest-related protists to animals and our likely last unicellular ancestors). So, both protist-to-plant and protist-to-animal transitions look pretty reasonable on this alone.

Sources: here, here (papers), here for cell specialisation, here (video) and here (long video).

Darwin’s Finches, revisited 150 years later

and their relatedness.](/post/evolution-evidence/darwin_finches_huc9f0c74ccc6b0edd3f76f749474efb18_1027661_d5bc65dbafe1fe4643eeb743ec5d8470.webp)

This is a textbook example of bird microevolution from Darwin’s 1830s voyage of the Galápagos islands, but studies from the 1980s onwards have identified speciation in the ‘Big Bird lineage’ on Daphne Major island. Regional droughts which reduce seed dispersal to the islands, such as those that occurred in 1977 and 2004, as well as arrival of competitors, were found to be drivers of selection for beak stiffness. The new lineage of finches reproduces only with its own.

Sources: here (paper), here (article) and here.

Salamanders, a classic ring species

A ‘ring species’ is a rare and aesthetically-pleasing display of speciation wherein a population living outside a circular barrier (e.g. the sands surrounding a lagoon) sequentially mutates and migrates around the circle, so that when they meet up again on the other side, they cannot interbreed. One of the most well-known cases of this is the salamander Ensatina eschscholtzii, which spread around the edge of a dry uninhabitable valley in California. A total of seven subspecies of these salamanders developed around the circle, two of which cannot interbreed with each other. Actually, this case is not a ’true’ ring species, as the diversification process was more complex than simply continuously spreading around the circle, but it still does represent an example of complete speciation.

This process took millions of years, so it wasn’t directly observed, but the studies showing interbreeding capability of neighbouring subspecies despite isolation between two were done in the present, so it’s pretty conclusive as to what happened.

Source: here.

Greenish Warbler, another ring species

.](/post/evolution-evidence/greenish_warbler_hu7125a4296bfb02f88d7f225a327d52a2_1340200_24824ba8181b2f3e73982f6584f875e3.webp)

This is another ring species, and one that is closer to a true ring species than the Californian salamanders (though still not a perfect ring species - it seems there are no simple true cases!). These birds, Phylloscopus trochiloides, inhabit the closed boundary of the Tibetan Plateau, of which two reproductively isolated forms co-exist in central Siberia. Genetic studies find some degree of selection against interbreeding, contributing to the speciation process. This happened over about a million years, so we’re using the phylogenetic species concept here.

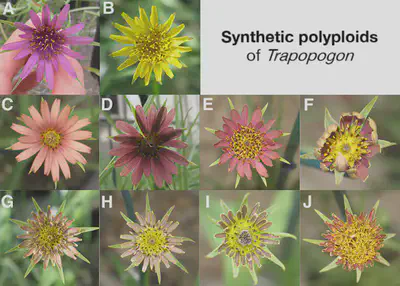

Hybrid plants and polyploidy

Tragopogon miscellus are ‘allopolyploid’ plants (multiple sets of chromosomes, some from another species) that formed repeatedly during the past 80 years following the introduction of three diploid species from Europe to the US. This new species has become established in the wild and reproduces on its own. The crossbreeding process that we have used to make new fruits and crops more generally exploits polyploidy (e.g. cultivated strawberries) to enhance susceptibility to selection for desired traits.

Source: here.

Alligators and chickens growing feathers

In the lab, a change in the expression patterns (controlled by upstream genes) of two regulatory genes led to alligators developing feathers on their skin instead of scales. These occur via the ‘Sonic hedgehog’ (Shh) pathway, one of the many developmental cascades activated by homeotic genes. The phenotypes observed in these experiments closely resembled those of the unusual filamentous appendages found in the fossils of some feathered dinosaurs, as if transitional.

A similar thing has been done to turn the chickens’ scales on their feet into feathers, this time with only one change to the Shh pathway, showing how birds are indeed dinosaurs and descend within Sauropsida.

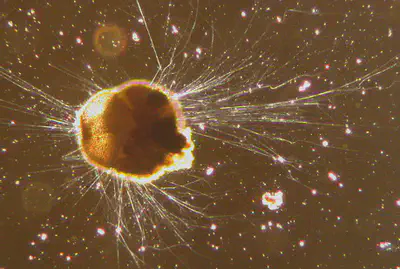

Endosymbiosis in an amoeba

There is excessive evidence that the organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts (and more recently discovered, the nitroplast) found within extant eukaryotes were originally free-living prokaryotes, which became incorporated (endosymbiosis), but no such thing had been observed, until now. The bacterial order Legionellales are responsible for Legionnaire’s disease and live in water, but are uniquely able to survive and reproduce even after being ’eaten’ by some amoebae before returning to free-living conditions.

In the lab, it was found that some strains of wild amoeboid protists in clade Rhizaria, class Thecofilosea, were transmitting fully-incorporated Legionellales vertically by cell division. Extracellular transmission of bacteria was not observed, indicating mutualistic endosymbiosis, and genetic studies confirmed divergence of the endosymbiont via a shrinkage of its genome (as expected) and gene translocation to the protist’s nuclear DNA.

Eurasian Blackcap

.](/post/evolution-evidence/eurasian_blackcap_hu9a8e6a6672f0b7ad2051aa41a3de533d_944740_a1be45bd2045cf9d811fd1d37cc9e69b.webp)

The migratory bird Sylvia atricapilla typically flies either south-westerly towards Spain or south-easterly into Asia as winter approaches in Europe, but the rise of birdwatching as a hobby in the UK in the 1960s led to a new food source in Britain that the westerly-flying birds could migrate to. This change is known to be genetic in basis. Those that instead migrated to the British Isles in winter returned home 10 days earlier (due to the shorter distance to central Europe) than those that went towards Spain, and therefore would mate only with themselves (sympatric speciation). The UK-migrating group now has rounder wings and narrower, longer beaks, over just ~30 generations, and although genetic differentiation has not yet reached the point of preventing interbreeding entirely, these birds are quite clearly well on their way to speciation.

Another collection of observed cases of macroevolution is given here and here, known for several decades now.

Marbled Crayfish

https://www.surescreenscientifics.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Marbled-Crayfish-1-min.pdf

Cichlid fish

2. GENETICS

Genetic similarity between organisms is indicative of evolutionary relatedness, since mutation accumulate within lineages and are passed on to offspring. Studying the genomes of extant life therefore informs evolutionary history.

Pseudogenes

29.49% of the human genome is made up of pseudogenes, most (but not all) of which are non-functional (either not transcribed or transcribed levels too low for functionality).

GULO (L-gulonolactone oxidase): GULO is mostly conserved across the animal kingdom, with a similar gene GLDH appearing in other eukaryotes. It encodes for the enzyme synthesising vitamin C (ascorbic acid) from L-gulono-γ-lactone (in turn from glucose). However, in haplorhines (tarsiers, monkeys, apes: including humans), GULO has been lost, so we have to source our own vitamin C from our diet (or die from scurvy). GULO has also been lost independently in the bat genus Pteropus and guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus).

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00239-024-10165-0

NANOG (homeobox protein).

DDX11L: 6 copies in chimpanzees, 4 copies in gorillas, and 2 copies in macaques

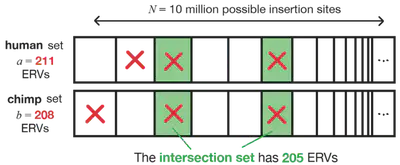

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs)

If a retrovirus infects a germline cell (usually a sperm cell progenitor e.g. spermatocyte), then the viral genome will be inserted inside the germline DNA. When the sperm cell multiplies and fertilises an egg, the viral genome can be passed into the offspring. As long as the virus remains in its dormant state, it will not cause any problems and may become permanently fixed in the genome due to genetic drift. ERV sequences become quickly methylated on inheritance and have their LTRs mutated so cannot jump around the genome any more like retrotransposons, becoming fixed in position before speciation occurs. The viral genome is then said to be ’endogenous’ and will appear in all subsequent descendants of the first infected individual.

We can look for traces of these ’endogeneous retroviruses’ (ERVs) in modern genomes. ERVs can be identified by the ’long terminal repeats’ (LTRs) at either end of the genome, and the gag, pol (contains the reverse transcriptase, integrase and protease) and env genes for the viral proteins. Since ERVs insert themselves mostly randomly into the genome, if ERVs are found in extant species with exactly the same positions and identities, it can be safely assumed to be inherited from a common ancestor as the chance of a coincidental separate identical insertion is negligible. Most (at least 90%: source) ERVs are non-functional, so the common creationist argument of “common design” loses its validity for ERVs. Some ERVs can be exapted for use by the organism at a later time as a de novo gene, as new promoters form readily by random mutation alone.

For example, one type of ERV that is found in both humans and chimpanzees is called HERV-W. For this particular ERV, there are 211 of them in humans, 208 of them in chimps, of which 205 of are found in identical locations of both genomes (source). This tells us that the human-chimp common ancestor had the 205 HERV-W insertions that we both have, and then a few more were acquired more recently after the split. The env gene of HERV-W remains transcribable, and produces a protein called syncytin-1, which has been co-opted for use in the formation of the placenta, but can also act as an immunogen in multiple sclerosis.

To drive the point home, we can estimate explicitly the probability that two genomes would just so happen to have the observed 205 identical insertions, when one of them has 211 and the other has 208, if the ERVs are inserted randomly without any common ancestry (the null hypothesis). We assume a total of

We can solve for the required probability with combinatorics:

since there are

I believe this model is more accurate than the calculations performed by some other sources (e.g. Stated Clearly uses a binomial distribution, source here, video here), although it doesn’t affect the conclusion we make.

Now, we sum over this probability between

As intuited, the odds of getting the observed HERV-W distribution in humans and chimps without common ancestry is ridiculously tiny: about 1 in

CpG islands

Heat shock proteins

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00182743

Chromosome 2 fusion in the human lineage

Sources: here, here and here and here (paper).

Beneficial mutations in human evolution

The full genomes of Homo sapiens, Homo neanderthalensis and Denisovans are available, as well as all extant primates, which helps us reconstruct evolutionary relationships and study the origins of individual genes.

Most recent survey of genomes: here

Paranthropus proteins: here

Human-specific mutations affecting brains and intelligence:

- ARHGAP11: the basal form, ARHGAP11A, encodes the protein RhoGAP with nuclear localisation, found in all extant non-human mammals. A partial duplication ~5 MYA seen in Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Denisovans led to them additionally acquiring ARHGAP11B, which shows mitochondrial localisation instead. It promotes basal progenitor cells (BP cells) and increases the neocortex size significantly. Sources: here, here and here.

- TKTL1 (transketolase-like 1): modern Homo sapiens has an arginine point mutation (K261R) while Neanderthals, Denisovans, archaic Homo sapiens and other extant primates have the lysine form. The human gene promotes production of basal radial glial cells (bRG cells, neural stem cells), significantly increasing upper-layer cortical neuron production and the size of the brain’s gyri (ridges) in the frontal lobe. Source: here and here (video)

- NOTCH2NL: NOTCH genes prolong proliferation of neuronal progenitor cells and expand cortical neurogenesis. Many of these genes are duplicated in Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Denisovans to varying degrees. Source: here

- SRGAP2: Partially duplicated to SRGAP2B 3.4 MYA, followed by two larger duplications at 2.4 MYA and 1 MYA. Source: here and here.

- FOXP2: Linked to development of speech and language skills. Source: here.

- TBC1D3: another human-specific gene contributing to the frontal cortex. Source: here

Human-specific mutations affecting muscles and biomechanics:

- PPARGC1A and MHY7: promotes a higher proportion of slow-twitch muscle fibres rather than fast-twitch.

- GDF8 (myostatin): negatively regulates skeletal muscle growth.

- MYH16: changes the musculature of the jaw. Source: here.

- HACSN1: a developmental enhancer leading to limb and digit specialisations. Source: here

Examples from recent human evolution (<300 kYA): source

- ADH1B (alcohol dehydrogenase): the SNP Arg48His is more common in East Asians due to rice domestication, and reduces the risk of alcoholism. Another SNP Arg370Cys occurs in Africa which reduces alcohol dependence.

- PDE10A: leads to enlarged spleens in the Bajau people. The spleen is a reservoir of oxygenated red blood cells, allowing them to hold their breath for longer (hypoxia tolerance) while freediving. Source: here.

- NOS3 (nitric oxide synthase) and others for high-altitude adaptation: in three distinct populations (Tibetans, Andeans and Ethiopians), multiple different mutations in a variety of genes lead to hypoxia tolerance, allowing for their survival at high altitudes.

- Sickle cell trait: in regions of Africa where malaria is prominent, carrying one copy of the recessive sickle cell anaemia allele confers resistance to the Plasmodium parasite. While there are associations of sickle cell trait to other medical conditions, many people with the trait remain healthy, making it net beneficial in malaria-endemic regions. Source: here.

- White skin colour: in northern Europeans, the SLC24A5 gene has an SNP Ala111Thr that leads to decreases melanin expression and hence lighter skin pigmentation, which is beneficial for vitamin D synthesis in the low-sunlight high-latitude regions.

Interesting neutral mutations in recent human evolution

In some of these cases, no harmful effect is observed despite what is typically thought of as a ’loss of function’ (e.g. gene deletion). These result in variation in the population, and may serve as a substrate for future selection, or simply be neutral. Additionally, what is neutral in a current environment may become beneficial in a future environment.

- Blue eyes: leads to blue eyes instead of brown, due to a mutation in OCA2. It has been shown that all blue-eyed people today share a common ancestor living around 6-10 kYA (a perfectly resolved founder event). This is presumed to be a neutral mutation, with the possibility of sexual selection. Source: here

- Retention of the median artery into adulthood: normally considered an embryonic structure that regresses around the 8th week of gestation, but it has been found to be retained with increasing frequency in recent times. Source: here.

- Palmaris longus muscle: a small muscle in the forearm that is absent in about 10-15% of the population, with negligible loss of overall grip strength or hand function (there is a small reduction in pinch strength in the 4th and 5th fingers).

- ABCC11: the T/T allele carried by nearly all Koreans and many other East Asians is non-functional, preventing its expression. This leads to dry flaky earwax and significantly reduced body odour, even after sweating and exercise. Source: here

- Third molar agenesis: wisdom teeth are becoming less common due to humans eating softer foods that have been processed for ease of consumption, no longer requiring large strong jaws. Associated genes include PAX9, AXIN2, MSX1 and THSD7B. Source: here

Human lactose tolerance

In lactose intolerant people (~65% of humans worldwide), the ability to digest lactose is lost during adolescence. The lactase enzyme is required to metabolise lactose into glucose and galactose. Without lactase in the small intestine, lactose remains available for the bacteria in the large intestine which ferment it, leading to fatty acid and gas production, causing symptoms of lactose intolerance.

The LCT gene codes for lactase, and has a low-affinity promoter. The MCM6 gene, found upstream on chromosome 2, codes for a subunit of helicase (an unrelated protein used in DNA replication), and an intron of MCM6 contains an enhancer for LCT. Transcription factors that bind to the LCT promoter include HNF1-α, GATA and CDX-2, while Oct1 binds to the LCT enhancer.

In mammals, most metabolic genes except lactase are expressed at low levels early in development as nutrients are provided primarily by breast milk, but during adolescence, as these other genes are promoted, low-affinity promoters like LCT are outcompeted, sharply reducing LCT expression. In lactase persistence, point mutations to the LCT enhancer result in an increased affinity for the LCT promoter, allowing it to remain competitive for transcription throughout life, allowing lifelong lactase synthesis. So, this is not a loss of regulation or function, as routinely claimed by ID advocates. Some mutations also reduce the age-related DNA methylation of the enhancer. Lactase persistence has evolved independently with several SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) under strong positive selection in the past 10,000 years of human history, primarily in societies that had dairy farming and pastoralist agriculture.

Sources: here and here (video)

Herbicide and insecticide resistance

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-3180.2007.00581.x

https://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.0030205

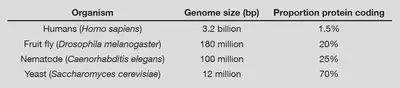

Genomics

The complete genomes of many extant species have been sequenced. Projects in bioinformatics aim to describe and compare the contents and functions of these genomes.

- The Human Genome Project (2003) found that there are about 22,300 protein-coding genes in humans (similar to other mammals) and contains a large number of repetitive sequences (low copy repeats).

- The Chimpanzee Genome Project (2013) revealed that humans and chimpanzees share 99% sequence similarity in protein-coding regions, and 96% sequence similarity across the full genomes, both higher than humans and any other animal.

, [here](https://www.reddit.com/r/DebateEvolution/comments/18uonlm/human_and_chimpanzee_genetic_similarity_an/) and [here](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ryBKzJE24Hs).](/post/evolution-evidence/mammal_genome_comparison_huad3c33b20de65bf44ea02984f096a1dc_84920_c4d6f2ef4f1836de17d665d0abb921d9.webp)

- The ENCODE Project (2021) found that, in humans, about 75-80% of the genome is transcribed into RNAs. However, most of this transcription is either 1) spurious (too low-level to have meaningful biochemical functionality), or 2) forming transposons (LTRs, ERVs, SINEs, LINEs), which simply ‘jump’ around the genome with no useful function.

- Among human non-coding DNA, 5% is for gene-related regulatory sequences (promoters, enhancers…). 20% is for introns in genes, most of which serve no function. The rest is completely non-functional (sometimes called ‘junk DNA’, although historically this term was incorrectly applied to all non-coding DNA).

E. Coli citrate metabolism in the LTEE

The Lenski long-term evolution experiment (LTEE) is a famous study that’s been ongoing since 1988, following 12 initially-identical but separate lines of E. coli bacteria over 80,000+ generations thus far. There are no external selective pressures in the LTEE, so the experiment is about what the bacteria could do on their own. Among the outcomes include de novo gene birth from non-coding DNA and near-complete speciation into two variants with differing colony size, but most importantly, one line evolved the ability to eat citrate (Cit) in aerobic conditions, a trait universally absent in wild-type E. coli. This led to an immediate rise in population density.

Contrary to the claims of top intelligent design (ID) proponents (e.g. Dr Michael Behe), this is not merely due to the loss of regulation of CitT (the relevant gene) expression, which would constitute a loss of function. In fact, the CitT gene was in an operon controlled by an anaerobically-active promoter, and underwent gene duplication, and the duplicate was inserted downstream of an aerobically-active promoter. This is therefore a gain of functionality. However, this duplication conferred a negligible (~1%) fitness advantage in the experiment, and at least two other mutations (in an intron of the dctA gene after, and in the gltA gene before) were shown to be necessary to obtain fully-functional citrate metabolism. This therefore meets the criteria for an “irreducibly complex” trait - and it’s one that emerged under experimental conditions normally adverse to innovation (stasis - promotes stabilising selection)!

In an amusing attempt to refute this, ID advocate Scott Minnich (works at Discovery Institute, a politically-motivated creationist organisation) reproduced the experiment in 2016 with a new colony of wild-type E. coli and found the same Cit+ trait emerge! And this time, much faster than in the LTEE, via the same pathway, featuring CitT and dctA. The abstract of their paper ends rather desperately: “We conclude that the rarity of the LTEE mutant was an artifact of the experimental conditions and not a unique evolutionary event. No new genetic information (novel gene function) evolved.” - despite us having disproven that already.

Sources: here, here and here (video).

Tetherin antagonism in HIV groups M, N and O

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that infects human immune cells expressing the CD4 surface protein, such as helper T-cells and macrophages. Once inside cells, HIV-1’s Nef and Vpu proteins work independently to reduce the expression of CD4, which prevents ‘superinfection’ (two viruses infecting the same cell) and decreases the chance of an immune response. The slow death of helper T-cells leads to a weakened immune system.

If HIV infects a different immune cell, such as a macrophage, the virus’ escape is hampered by the high expression of a cell protein called tetherin. This limits the virulence of HIV in macrophages. However, some strains of HIV-1 have evolved ways to antagonise tetherin using their Vpu and Nef proteins, giving them a second function in addition to retaining their CD4-degrading activity in helper T-cells:

- In HIV-1 group M, tetherin antagonism occurred with 4 concurrent point mutations in Vpu.

- In HIV-1 group N, weak tetherin antagonism occurred with 4 different point mutations in Vpu, but it led to loss of CD4-degrading activity.

- In HIV-1 group O, this occured with just 1 point mutation in Nef (C169S).

So, the same trait evolved two ways (in groups M and O), one of which (group M) was supposedly ‘irreducibly complex’: it was a beneficial trait that required sequential mutations in already functional proteins. Group M now dominates worldwide HIV cases while group O resides mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and group N is very rare.

HIV also simultaneously demonstrates observed ‘macroevolution’ (to the extent that it can be defined for viruses, which are not life). HIV has a zoonotic (animal) origin, as it came from chimpazees’ endemic SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus) strain. SIV is rampant among non-human primates, but each species has evolved to tolerate its own strain. It became human transmissible as HIV in the early 1900s due to mutations that allowed it to bind our CD4 receptors, which differ slightly between humans and other apes, and is far more virulent in humans.

Extra sources: here.

Re-evolution of bacterial flagella

The flagellum is the flagship allegedly irreducibly complex structure, cited ad nauseum by ID advocates. Since it is the one that has been talked about the most, it has also attracted a lot of attention from real scientists who have promptly disarmed it. In one experiment, the master regulator for flagellum synthesis (FleQ) was knocked out, leaving all of the other flagellar genes intact. But under selective pressure for motility, it was found that another transcription factor that regulates nitrogen uptake from the same protein family (NtrC) was able to ‘substitute’ for FleQ, essentially by becoming hyperexpressed, so there’s so much NtrC in the cell that some of it binds to the FleQ-regulated genes and activates them too.

This is an incredibly reliable two-step process, after 24-48 hours we get a mutation in one of the genes upstream of NtrC that leads to higher expression and activation, then within 96 hours of the start we see a second mutation, normally within NtrC itself, that helps fine-tune the expression.

Source: here.

3. MOLECULAR BIOLOGY

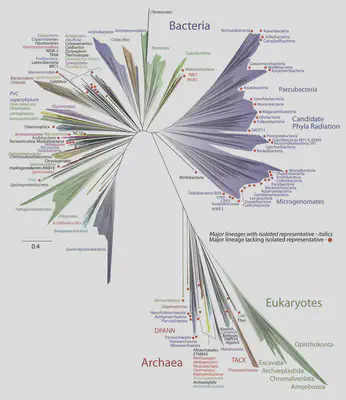

rRNA phylogenetics

For the earliest stages in evolution (unicellular organisms), fossils are scarce, and genomes have mutated beyond recognition in many places, so we must look more carefully. The ribosome is a key piece of cellular machinery that translates RNA into proteins, whose functionality is so tightly constrained that it can be used to measure relatedness across the whole tree of life.

A surprising result of this analysis is according to ribosome similarities, all eukaryotes descend within archaea. This strongly supports the hypothesis of endosymbiosis, where an ancient archaea cell and an ancient bacteria cell merged to become a eukaryotic cell, with the archaea providing the genes that went into the nucleus.

Antibiotic resistance

A striking visualisation of antibiotic resistance is a video of an experiment done by Harvard Medical School, where they created four zones with antibiotic concentrations increasing by a factor of 10 each time. The bacteria would spread outwards up to the boundaries. Most would go extinct, but a few mutants from some populations would survive and move into the next zone. When all zones had been reached, the colonies traced out the pattern of their phylogenetic tree.

. Paper: [here](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aag0822).](/post/evolution-evidence/antibiotic_phylogeny_hu61e847926f422580e68087a5a4a947db_1552889_00c3ccfe2c4c88e26cb6fbcaf3658512.webp)

Despite being a highly tangible example of evolution in action, antibiotic resistance is rarely described as “evolution” in the medical literature (sources: here and here).

Nylon-eating bacteria

Nylon is a synthetic insoluble semi-crystalline polymer of 6-aminohexanoic acid, invented in 1935 and used in a variety of consumer products.

In 1965, Japanese researcher Takashi Fukumura found that 11 bacterial strains in the wastewater of the Toyo Rayon (today Toray) 6-polyamide factory in Nagoya were able to grow on ε-caprolactam, the cyclic amide precursor to Nylon 6. One more species, Corynebacterium aurantiacum, also was found to be able to metabolise linear and cyclic 6-aminohexanoate oligomers. Another group of researchers 4 years later found a strain from the phylum Pseudomonas in the waste water of the same factory that was also able to metabolise 6-aminohexanoate oligomers.

In 1974, Hirosuke Okada conducted research on Flavobacterium also living in the wastewater. He found that the strain Flavobacterium sp. K172 was able to metabolise ε-caprolactam, 6-aminohexanoate and cyclic aminohexanoate-dimer as well as the linear di- bis hexamers of 6-aminohexanoate. The new enzymes had no activity on biologically derived molecules having similar chemical structures.

After some debate in the literature, it has been concluded that one of the new ’nylonase’ enzymes (6-aminohexanoate-dimer hydrolase, EC 3.5.1.46, EII, NylB, P07062) evolved in a two-step process:

- a gene duplication in Flavobacterium to produce a protein named EII’

- base substitutions of EII’ to produce EII.

It has been shown (Negoro et al., 2007) that EII’ has 88% sequence similarity with EII, but only 0.5% of the catalytic activity. Just two point mutations in EII’ found in EII were needed to raise the activity to 85% of EII.

De novo promoters and orphan genes

DNT metabolism in bacteria

https://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/dover/pf.html#p84

Antifreeze proteins

Living in cold environments poses a serious challenge to poikilothermic (not thermally regulated) life, as the water in cells may freeze, halting all metabolic processes and killing the organism. Antifreeze proteins have evolved as a solution: when an ice crystal nucleates, the protein’s ice-binding domain attaches to the surface of the crystal, arresting its growth. The ice-binding domain is a regular arrangement of polar hydrophobic amino acids with a separation very close to the lattice constant of ice, creating an ideal fit for hydrogen bonding and Van der Waals’ forces at the interface.

The β-helix motif found in these proteins is common enough in natural secondary structures that it has convergently evolved many times: ice restructing proteins making use of it are known in the winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus), the spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana), the mealworm beetle (Tenebrio molitor), the snow flea (Hypogastrura harveyi), some sea ice-living diatoms (Fragilariopsis cylindrus) and even some plants like winter rye (Secale cereale). The spruce budworm antifreeze can inhibit freezing as low as -30 °C, below even the supercooling limit of liquid water, but some others only work down to about -5 °C, allowing only marginal additional exploratory capacity in cold environments. These antifreeze proteins have different amino acid composition but all perform the same function. Some protein sequences resemble C-type lectins or sialic acid synthase.

In (Zhuang et al., 2019), it is shown that the antifreeze protein from the northern codfish originated from non-coding DNA, in a process involving frame shift mutations (by 1-nt deletion), duplications and de novo gene birth. Comparison to psueodgenes in closely related species is used to support this. This likely evolved in response to the cyclic northern hemisphere glaciation that began in the late Pliocene (about 3 MYA).

Sources: here, here (video) and here (video).

Cytochrome c oxidase

The cytochrome c oxidase (COX) enzyme is a famous and ubiquitous component of the electron transport chain for respiration, found in bacteria, archaea and the mitochondria of eukaryotes. Since COX is universally conserved, we would expect it to be more similar in closely related organisms, and less so in more distant ones. In fact we find experimentally that there is a strong correlation between the number of amino acid substitutions in the COX enzyme and the time since the divergence of the species. This is a powerful demonstration of the ‘molecular clock’, which gives us an estimate of the time taken for two genomes to have mutated away from a common ancestor, helping us put a time scale onto our evolutionary tree model.

Source: here

4. PALEONTOLOGY AND BIOANTHROPOLOGY

NOTE: paleontology is the study of fossils, but since human evolution is a common topic, I include lots of human-specific evidence here from the broader field of bioanthropology, which includes non-fossil evidence.

Fossils are remnants of long-dead life and provide a tangible record of the distant past. We can compare fossilised structures and estimate fossil age using radiometric dating of nearby ash layers to help piece together evolutionary lineages, which can be cross-checked against more precise genetic studies. Taken together, they serve as signposts of how lineages changed over time.

Some of the most obvious evidence for evolution is ’transitional fossils’. Technically, all fossils are ’transitional’, since all life is evolving at all times, but some lineages offer especially clear changes in form over deep time, when ordered by their radiometric dates or strata.

Horse evolution

(Bruce J. MacFadden, Fossil Horses - Evidence for Evolution. *Science* 307, 1728-1730 (2005). doi:10.1126/science.1105458).](/post/evolution-evidence/horse-fossils_hu09483c634d21f4cef7de49e3c74753b5_953653_ca8b8ea592ee1e7b05098fe63d562859.webp)

Bird evolution

.](/post/evolution-evidence/bird_fossil_hu1ca888a831b451de71ae455244df9aec_2676355_2efff30c2627107db6bafbf3082932b3.webp)

Whale evolution

. Many other species with nearly complete fossils are known: e.g. [here](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolution_of_cetaceans).](/post/evolution-evidence/whale_fossils_huf29ce38d64c98f8c107428e5f99992df_4415588_d35f17474e7e738a0ff676355af9f252.webp)

. **(c)**: The post-cranial fossil material found from *Indohyus*. **(d)**: Reconstruction of postcrania and artist's impression.](/post/evolution-evidence/indohyus_fossils_hu61c939bece30306a13b349ff092c3b24_2296788_781352e25589f41f4db6d03419d693ec.webp)

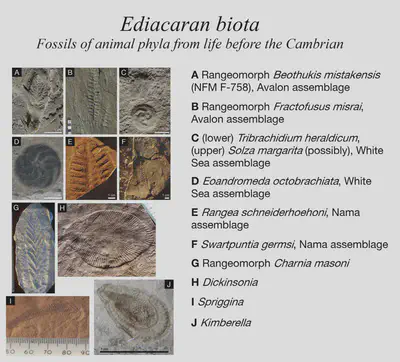

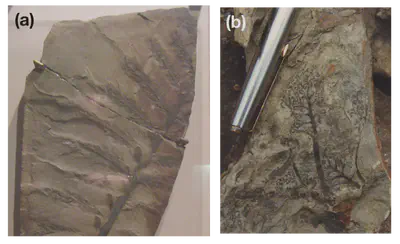

The earliest animals

Plant evolution

Plant fossils has its own field of study: paleobotany.

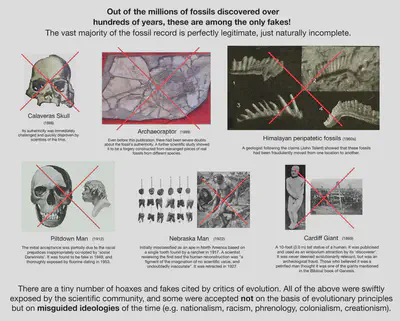

Fake fossils?

The fact that these fraudulent cases are so rare, are so thoroughly well-scrutinised when they do happen, and are always rejected by the scientific community, serves as reassurance that the vast majority of the fossil record is in fact perfectly reliable, just naturally incomplete.

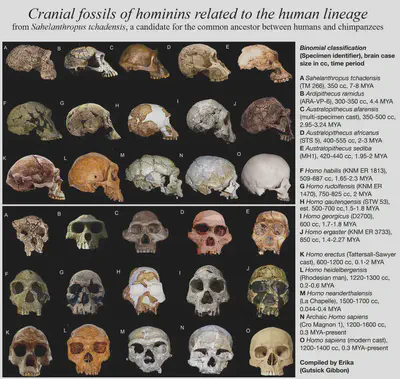

Human evolution

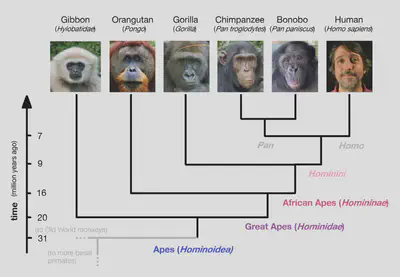

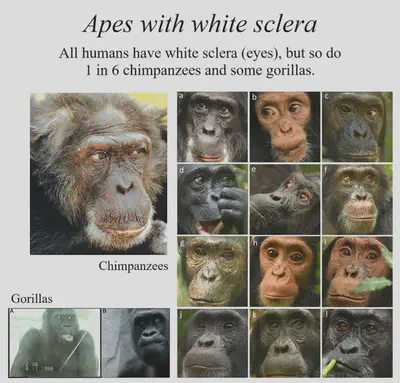

Human evolution is an especially well-studied topic. We are primates and great apes, and there is an abundance of fossils to tell us how our lineages developed over time. Genus Homo arose from the prior genus Australopithecus about 2.5 million years ago, and following a period filled with numerous species of Homo, our species Homo sapiens emerged about 300,000 years ago. Our close relationship with chimpanzees, gorillas and bonobos make them great for studying behaviour, too.

Primate anatomy and taxonomy

The study of extant primates can also give us clues into our shared past.

In 1698, English anatomist Edward Tyson dissected a chimpanzee and noted in his book that the chimpanzee has more in common with humans than with any other ape or monkey, particularly with respect to its brain.

In 1747, taxonomist Carl Linnaeus wrote to J. G. Gmelin, expressing (with circumspect forbearance) his conclusion that humans and other apes must, by the logic of his own nested hierarchies, belong to the same group, which he called Anthropomorpha. He writes:

As a natural historian according to the principles of science, up to the present time I have been not been able to discover any character by which man can be distinguished from the ape; for there are somewhere apes which are less hairy than man, erect in position, going just like him on two feet, and recalling the human species by the use they make of their hands and feet, to such an extent, that the less educated travellers have given them out as a kind of man.

I demand of you, and of the whole world, that you show me a generic character — one that is according to generally accepted principles of classification, by which to distinguish between Man and Ape. I myself most assuredly know of none…. But, if I had called man an ape, or vice versa, I should have fallen under the ire of all the theologians. It may be that as a naturalist I ought to have done so.

These early naturalists (along with many other Western contemporaries) recognised the similarities, but, living prior to Darwin, had no theoretical framework with which to explain them.

Primate behaviour

Primate behaviours are stunningly reminiscent of human behaviours.

Many non-human primates display a clear ’theory of mind’ (the understanding that others’ beliefs, desires, intentions, emotions and thoughts may be different from one’s own). Primatological studies find they:

- warn unaware group members of danger (Crockford et al., 2012)

- preferentially comfort bereaved mother chimps (Goldsborough et al., 2020)

- mediate and resolve fights they were not involved in (de Waal, 2004)

- use tools extensively, such as in nut cracking, termite fishing, spearing bushbabies for hunting etc. (Gibbons, 2007 and Hicks et al., 2019)

- provide a group mate with tools they need for a task they are not involved in (Yamamoto, Humle & Tanaka, 2009)

- use plants containing medicinal compounds to heal serious facial wounds, chewing them up and packing them in (Laumer et al., 2024)

- exhibit reconciliation, consolation and empathy

- mourn their dead (source: here)

- engage in vicious warfare against other groups, torturing rival males to death and assimilating rival females into their group (Wilson & Wrangham, 2003)

- conspire to instigate violent coups against alpha males (Jensen, Call & Tomasello, 2007)

- understand justice and fairness, with a similar level of prosociality as human toddlers (Proctor et al., 2013)

- easily pass the ‘mirror test’ (recognise themself in the mirror and use it to groom themselves)

- rescue nonrelated group members who are in mortal danger e.g. drowning in deep water (Fouts & Mills, 1997).

Primates also have complex language capabilities. Gelada vocalisations follow fundamental linguistic rules of grammar called Zipf’s law and Mezzarath’s law (Gustison et al., 2016), Campbell’s monkeys and panins both use syntax and grammar (Ouattara, Alban & Klaus, 2009). Chimpanzees and human toddlers have a ~90% overlap in ‘innate’ gestures (Kersken et al., 2019)

Many of these behaviours were at one point (even recently) thought to be the unique characteristic of humans that sets us apart, but in fact they are merely differences in degree rather than kind.

Many primatologists doing fieldwork regularly observe the ‘humanity’ in chimpanzees in particular.

Bipedalism in Hominins

Walking up on two feet (bipedalism) is a trait unique to humans today among the primates, so studying how this evolved is important. The suite of characteristics indicative of bipedalism, which originated in late Miocene hominids, is:

- Anterior foramen magnum*: skull rests on the top of the spine.

- Sagittally-oriented iliac blades*: pelvis rests upright

- Valgus knee (bicondylar angle)*: femur angled to keep knees in line.

- In-line hallux: the big toe is aligned with the other toes, aiding in walking.

- Bowl-shaped pelvis: supports the visceral organs around the abdomen.

- Lumbar lordosis (S-shaped vertebral column): supports upright posture.

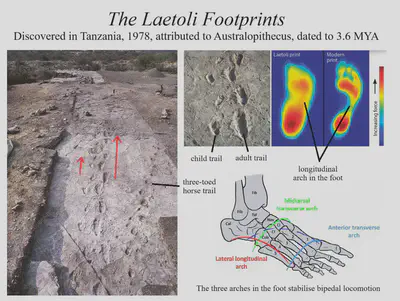

- Arched foot: three arches (medial, lateral, transverse) in the feet act as shock absorbers in walking.

* strongest indicators, since these biomechanically prevent quadrupedalism.

Fossils of extinct primates can be analysed to see whether these traits are present, allowing us to trace the gradual evolution of bipedalism.

Morphology and biomechanics are linked by causal morphogenesis (Wolff’s law).

Taxonomy of Australopithecus and Homo habilis

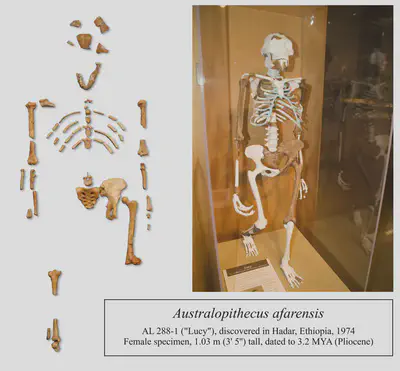

Our genus, Homo emerged from one of the coexisting species of the genus Australopithecus. Based on the available fossil record, this transition appears to be quite subtle: the brain case sizes overlap, both can use stone tools, both have similar dentition (teeth), and biomechanics studies indicate both were mostly bipedal (though A. afarensis only had two arches plus a less-curved third arch in the foot, suggesting habitual bipedality, while H. habilis had three fully formed arches, suggesting full obligate bipedality). This high degree of similarity has even led to some paleoanthropologists to suggest that H. habilis should in fact be Australopithecus habilis. Although this has not been formally adopted, the challenge of a clear-cut taxonomic classification demonstrates the highly transitional nature of these species.

Another example of this comes (ironically) from creationists, who are ideologically required to divide the hominin fossil record into two allegedly mutually exclusive groups: the ‘ape’ kind and the ‘human’ kind. However, six famous hominin cranium fossils of H. habilis and early H. erectus (KNM-ER 1813, Java man, Peking man, KNM-ER 1470, KNM-ER 3733 and Turkana Boy) were all classified by seven different creationists completely differently, precisely as expected of a ’transitional’ species without a true clear divide.

Neanderthals are not our ancestors

One of our closest relatives, the Neanderthals, went extinct about 40,000 years ago. Autapomorphies (uniquely defining traits) of Homo neanderthalensis include retreating cheekbones (zygomatics), the occipital bun, large nasal aperture, enhanced prognathism, enhanced brow ridges (supraorbital torus), platycephalic skull, angled squamosal suture, retromolar gap and an elliptical foramen magnum.

Significant hominin fossils, ichnofossils and artifacts

- Ardi: partial skeleton of Ardipithecus ramidus, 4.4 MYA, discovered in the Afar rift valley (Ethiopia).

- Little Foot (StW 573): near-complete specimen, Australopithecus africanus, 3.67 MYA. Found in the ‘Cradle of Humankind’ in South Africa, an area home to many other early hominins.

- Burtele foot: partial foot, 3.4 MYA, with a divergent hallux. Tentatively assigned to Ardipithecus ramidus, implying contemporaneity with Homo, Australopithecus, Paranthropus and Kenyanthropus.

- Taung Child: skull of a 3-year-old Australopithecus africanus, 3.3 MYA.

- Dikika Child (Selam): skull of a 3-year-old Australopithecus afarensis, 3.3 MYA.

- Lucy (AL 288-1): partial skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis, 3.2 MYA.

- Ledi Geraru mandible (LD 350-1): jaw assigned to basal genus Homo, 2.78 MYA.

- Mrs Ples: complete skull of Australopthecus africanus, 2.35 MYA.

- Dmanisi skulls: a set of skulls of Homo erectus, 1.81 MYA.

- Turkana Boy: near-complete young Homo erectus, 1.55 MYA.

- Peking Man: a Chinese specimen of Homo erectus, 500 kYA.

- East Asian archaics: a collection of late Homo erectus, archaic Homo sapiens and Denisovan specimens from China and surroundings, e.g. Dali man, Xiahe mandible, Harbin skull/Dragon man…

- Denny: teeth from a 13-year old female containing DNA, Neanderthal-Denisovan hybrid, 90 kYA.

- Laetoli footprints: two trackways, attributed to Australopithecus, 3.6 MYA. The indentations suggest a fully in-line hallux.

- Lomekwi stone tools: oldest stone tools, attributed to Australopithecus or Kenyanthropus.

5. GEOLOGY

Stratigraphy

The idea that rocks are deposited in layers (strata: older below, younger above) has been known since Steno in the 17th century (the ’law of superposition’). It is therefore usually the case that fossils found in deeper layers are older than those found above, serving as a rough guide to their age (a qualitative, relative dating method). However, other geologic processes like erosion, folding and faulting can disrupt this order occasionally, so more reliable references are needed.

Fossil species that are used to distinguish one layer from another are called index fossils, which occur for a limited interval of time. Usually index fossils are fossil organisms that are common, easily identified, and found across a large area. When a fossil is found, the nearest volcanic ash layers above and below it can be radiometrically dated, allowing us to bound the age of the fossil (tephrochronology).

In (Benton & Hitchen, 1997), the existing fossil record for 384 different clades all across the animal kingdom was surveyed and cross-referenced with their claimed evolutionary relationships. Using three different statistical metrics (Spearman’s rank coefficient, and two others dedicated to quantifying the presence of ‘ghost lineages’), it was found that all three falsify the null hypothesis (if the fossil record does not reflect the major patterns of evolution, there would be no evidence for congruence between the two sets of data in our random sample of cladograms).

Dendrochronology

Trees grow at a rate of approximately 1 ring in their trunk per year. By sampling the rings of multiple trees in a given region, and matching the thicknesses of each ring to the others, we can estimate the age of trees. This also allows for identification of missing or additional rings in a given tree, which are indicative of ecological disturbances (e.g. wildfires, insect outbreaks…).

Dendrochronology can be used to date wooden artifacts in archaeology from about 10000 years ago to present, since the last ring can be matched to the year it was cut down and used. The carbonised wood in charcoal can be both carbon dated and dendrochronologically dated, allowing us to cross-reference the two methods. We can also infer the climate conditions over its lifetime (paleoclimatology), inferring the past temperature, precipitation and cloud cover from the ring data. Climate data can also be cross-referenced against other sources (e.g. ice cores, sediment cores, historical records, meteorological data…). Examining the trace mineral content of the rings (e.g. carbon-12/13 ratio) provides further data on atmospheric conditions (stable isotope dendrochronology).

Source: here

Ice core dating

Varve chronology

Sedimentary layers in lakes and oceans.

Source: here

Paleomagnetic dating

, the rates of tectonic plate spreading at mid-oceanic ridges can be measured by recording the magnetisation of the sediment, which tracks the orientation of the geomagnetic field at its formation. This allows dating by measuring continental drift, and can calibrate magnetic analyses elsewhere by correlating with geomagnetic field reversals.](/post/evolution-evidence/geomagnetic_striping_hu5b1cf3e542791493dff0ea0d47ab6fe9_685745_7aba922bce26df11d418e8910ca06f2d.webp)

Iron-60 deposits in magnetofossils

Magnetotactic bacteria (MTBs) live a few centimetres below the sediment on an ocean floor. When sediment deposits on the ocean floor, the MTBs move up to maintain their depth. MTBs uniquely contain ferromagnetic particles which they use to passively align themselves to the geomagnetic field (magnetoreception). These particles are produced by the MTBs consuming iron hydroxide. When they die, their filaments retain the iron, forming a column of ‘magnetofossils’ where depth correlates with age.

In 1999, a new isotope of iron was discovered on the deep seafloor, iron-60 (

Calculations were performed to estimate the required position, distance and stellar mass of a potential supernova that could be responsible. A supernova observed to have occurred within the Tuc-Hor stellar group ∼2.8 Myr ago, 330 light years away, with supernova material arriving on Earth ∼2.2 Myr ago, was identified as the likely source. It was found that the iron-60 deposits are consistent with turbulent radioisotopic transport in dust grains originating from this supernova explosion.

Oklo natural nuclear reactor

Radiometric Dating with Uranium series

Coral dating: here

Radiometric Dating with Argon

Many volcanic rocks naturally contain the isotope potassium-40 (

Mount Vesuvius: Pliny the Younger was a Roman eyewitness to the Mount Vesuvius eruption, which he recorded as occuring in the early afternoon of 24th August, 76 AD, destroying Pompeii, Herculaneum and other Roman cities. In 1997, a piece of volcanic tephra from the region was subject to

Mount St Helens dating, using isochron dating

Radiocarbon dating of recent fossils and artifacts

The radioisotope carbon-14 is continuously formed in the upper atmosphere by cosmic rays, which can be absorbed by plant matter as CO

The Teide volcano in located in Tenerife (the Canary Islands). Stratigraphy found an age younger than 2000 years, while paleomagnetic dating found an age of 500 - 900 years. Historical records give an age of at least 500 years (European settlement began in 1494): Christopher Columbus reported seeing “a great fire in the Orotava Valley” as he sailed past Tenerife on his first voyage to the New World in 1492, interpreted to have been the Teide eruption.

Han van Meegeren was a Dutch painter during World War 2 and orchestrated a sophisticated art forgery. While his art skills were considered mediocre, he was able to create several convincing fakes of 17th century Vermeer paintings, some of which were sold to the Nazis in exchange for Nazi loot, including his piece The Supper at Emmaus. Van Meegeren confessed in 1946 and was found guilty with other evidence, but some doubt remained. In 1967, a study using the lesser-known

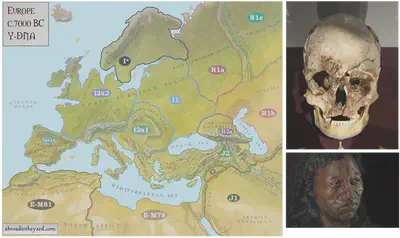

Cheddar man is a well-preserved skeleton of a Mesolithic (middle stone age) Homo sapiens found in the UK. DNA analysis found that he was likely a hunter-gatherer with bright blue-green eyes, slightly curly hair and black skin, with no lactase persistence. He probably arrived there via Doggerland, a low-lying region of Europe spanning between modern-day Britain, France and Germany, which sank under rising sea levels around 10-7 kYA, as the last glacial period ended. His Y-chromosomal haplogroup was I2a2, and 10% of British ancestry can be linked to Cheddar Man. Cheddar man was radiocarbon dated on two occasions to 8540-7990 BC and 8470-8230 BC, i.e. about 10,000 years ago.

Ötzi the Iceman is a copper-age naturally frozen mummy radiocarbon dated to about 3,200 BC, found in the Alps.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in 1947 in caves near the Dead Sea, and contained the earliest known records of the books of the Bible, written in Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic. Radiocarbon dating of the different scrolls gave dates from between 400 BC and 400 AD, which were mostly within 100 years of the dates estimated by analysis of the writing style (paleography).

The Shroud of Turin is a linen cloth with a distinctive imprinting that resembles the traditional face of Jesus Christ, which is said to have appeared on the cloth shortly after his crucifixion. However, spectroscopic analysis in 1978 suggested the imprint was painted on using a red ochre and vermilion pigment commonly used in medieval art. Additionally, in 1988, three independent radiocarbon dating laboratories all dated the cloth to between 1260-1390 AD, matching its first known appearance in church history in France.

Thermoluminescence dating

Electron spin resonance dating

Amino acid racemisation dating

Oxygen isotope ratio cycle (

The orbital monsoon hypothesis is based on the well-established concept of Milankovitch cycles, where long-term changes in Earth’s orbit (axial tilt, eccentricity and precession) result in changing frequencies, intensities and distributions of monsoons (intense wind and rain) on Earth due to changes in solar insolation. This has a strong impact on the climate of North Africa.

There are several lines of evidence for this model, including:

- The repeated occurence of sapropels (dark organic-rich marine sediment) in the plankton-rich sediment cores of the Mediterranean sea (indicative of low oxygen content due to freshwater influx from the River Nile).

- The repeated occurence of freshwater diatoms blown into the saltwater ocean sediment cores in the Atlanic ocean due to heavy monsoon trade winds.

- The cycle in isotopic ratios of oxygen-18 to oxygen-16 in calcite stalagtites/stalagmites in caves in China and Brazil, indicative of cycles in the water temperature due to the variable climate.

These cycles all have a period of about 22,000 years, closely matching the precession cycle of the Earth.

Sources: here (video).

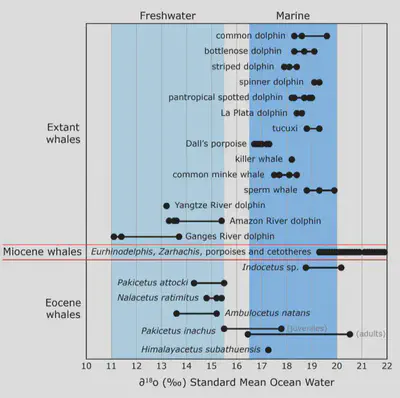

Saltwater and freshwater have different ratios of oxygen isotopes, due to more evaporation (depletion of oxygen-16) in the ocean. This means that we can learn about what sort of water an animal drank by studying the isotopes that were incorporated into its bones and teeth as it grew: higher oxygen-18 content implies saltwater (marine), while lower oxygen-18 content implies freshwaster (rivers and estuaries).

The isotopes show that Ambulocetus (transitional whale) likely drank both saltwater and freshwater, which fits perfectly with the idea that these animals lived in estuaries or bays between freshwater and the open ocean. Whales that evolved afterwards (Kutchicetus, etc.) show even higher levels of saltwater oxygen isotopes, indicating that they lived in nearshore marine habitats and were able to drink saltwater as today’s whales can.

Ice core paleoclimate data

6. BIOGEOGRAPHY

Ecological succession

This is fun one to bring up in the context of ‘creationism vs evolution’, as it refers to the macroscopic and very well-accepted process of ‘primary succession’. This describes the sequence that follows formation of a new region of land (well-studied in physical geography) as life moves in for the first time. The resulting ecosystems that form (in the ‘climax community’) are highly interdependent, such that removing one would collapse the whole food web, which is a defining feature of irreducible complexity. Yet, we watch it happen all the time - and this is something that must have happened regardless of whether creation or evolution is true!

Sources: here (article), here and here.

Prediction of Tiktaalik

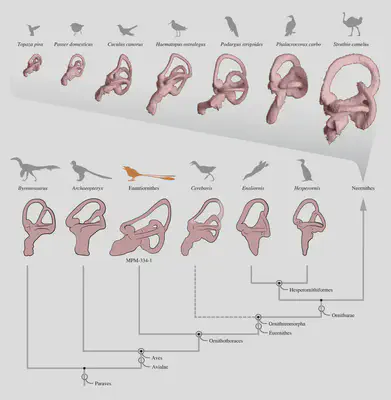

7. COMPARATIVE ANATOMY

.](/post/evolution-evidence/bird_ear_bones_1_hubc2eb35181f0972b2c749ada57ef817d_371485_278a5c02570e154f596b517b0a11d39d.webp)

Evolution of the vertebrate eye

Anatomical constraints in eye evolution: here

8. COMPARATIVE PHYSIOLOGY

Endosymbiosis in insects

Aphids have an endosymbiotic relationship with Buchnera Aphidicola bacteria. The bacteria break down nutrients that aphids need to survive but can only live within specialised ‘bacteriocyte’ structures in Aphids. But some aphids later in their evolution dropped B. Aphidicola and now have a yeast-like symbiont (YLS) that performs similar functions. These aphids still have the bacteriocytes but the YLS is located both inside and outside of them. So, these aphids have the same specialised structures as their cousins to host the bacteria but their symbiote is a fungus that doesn’t need those structures.

An example of higher-degree endosymbiosis is the Darwin termite (Mastotermes darwiniensis). The termite relies on a protist Mixotricha paradoxa to process the wood. The protists further rely on other bacteria living on its surface (each look like a thin hair that wiggles; symbiotic signalling in exchange for food). Within the protist, there is another endosymbiont spherical bacterium that digests cellulose in wood, releasing acetate for the protist. These bacteria have removed the need for M. paradoxa to have mitochondria, which have degraded into simpler organelles (hydrogenosomes and mitosomes).

Sources: here and Chapter 38 of The Ancestor’s Tale by Richard Dawkins.

Evolution of eyesight

As one of the most impressively complex sensory organs, the eye’s evolution has been especially well studied. Eyes in some form have evolved independently over 50 times, with vastly different structures and functions suited to each lineage.

Different types of eyes

- Retinal phototrophy: the retinal molecule is used by Haloarchaea in bacteriorhodopsin proteins to capture light energy via chemiosmosis. This is the key light sensor molecule needed for eyes, without any of the complex structures that evolved later.

- Eyespots: a simple light-sensitive organelle found in euglenids (unicellular photosynthetic protists), containing photoreceptor proteins. Without any nerve cells, the signal cascade on light detection results in flagellar movement, enabling phototaxis.

- Pit eye: one of the types of eyes found in invertebrates. A pit with photosensitive cells inside allows for some vague directionality of light detection.

- Pinhole camera eye: Found in Nautilus. More directional sensitivity, by nearly closing the pit, allowing light to enter only through a small aperture.

- Lens formation: Evolved 8 times. An inhomogeneous lens formed of crystalline proteins continuously bends light for focussing of light onto the photosensitive layer, giving a clearer image. It also corrects for spherical aberration.

- Multiple lenses: Found in Pontella. Males have three lenses; females have two. The extra front-facing lens in males is parabolic and corrects for spherical aberration of the other 5 surfaces. The retina has only 6 receptors.

- Telescoping lens: Found in Copilia. Two lenses work like a telescope with a point-like retina and only a 3° field of view. There is a horizontal scanning eye movements at <5 Hz, while the bottom apparatus (eyepiece + retina) moves in image plane of the ‘objective’. The prey (plankton) moves vertically, giving a second dimension of scanning.

- Corneal refraction in land animals: to correct for the air-water interface and spherical aberration. In humans, 2/3 of the optical power is in the cornea rather than the lens.

- Reflective concave mirror (argentea) in the scallop.

- Tapetum lucidum: a reflective layer behind the retina in many nocturnal and crepuscular mammals (cats, dogs, deer), aiding in night vision. A variety of structures and molecules are used.

- Compound eyes in insects and crustaceans.

- Nanostructured cornea anti-reflection surfaces for quarter-wave matching in moths.

- Binocular/stereoscopic vision in vertebrates.

- Trichromatic vision in primates. The Old World monkeys (including apes), as well as some female New World monkeys, are trichromatic, having gained a third cone from the dichromatic mammalian ancestral lineage.

Physical constraints in the evolution of the eye

Solar radiation is the main source of high-exergy free energy in the open biosphere, and its exploitation is therefore strongly selected for, such as in photosynthesis, photocatalysis and eyesight. At the molecular level, interaction with light requires a molecule that can absorb photons at the appropriate energy (wavelength), typically found in highly conjugated organic molecules. For wavelengths in the visible spectrum (most intense at Earth’s surface), these molecules include e.g. chlorophyll, retinal, 7-dehydrocholesterol, bacteriorhodopsin and phototropin.

With eyesight, there is the additional task of extracting information from the radiation, providing both thermodynamic and information-theoretic constraints on the evolution of the eye.

Radiation entropy maximisation: solar radiation is the main source of high-exergy free energy in the open biosphere, and its exploitation is therefore strongly selected for (e.g. photosynthesis). Solar radiation contains both energy and entropy, with slightly different Wien peaks for the two. The eye evolved to maximise the information extracted from the radiation, and the eye’s spectral sensitivity is optimised to the maximum entropy peak instead of the energy peak. Sources: here and here.

Utility-based coding: updates the opponent process theory explaining how S, M, L cone signals are encoded in the optic nerve and visual pathway. The new theory describes the optimal encoding of spectral information given competing selective pressure to extract high-acuity spatial information. Source: here

Principal components of reflectance spectra: the encoding of S, M and L into three channels can be explained by the observation that the three channels are the first three PCs in a PCA of the reflectance spectra of natural materials and scenes, encoding 98% of the total variance. This allows minimal information loss with the fewest number of channels, a consequence of the fact that the eye evolved to extract information from the environment. Source: here

Evolution of photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is another form of phototrophy which uses chlorophyll as the light-absorbing molecule. Like the eye, it is extremely complex today, but started out from simpler systems based on the same fundamental principles.

Photosystems in unicellular life

The two main parts of photosynthesis are Photosystems I and II:

- PSI: an electron transport chain using ferredoxin to generate NADPH.

- PSII: a water-splitting complex generating protons, which can be used for chemiosmosis in ATP synthase. Likely to have evolved first due to its simpler structure and immediate utility in generating ATP.

The ATP produced can then be used in a metabolic cycle to fix carbon dioxide into useful organic compounds.

The bacterial kingdom Bacillati contains a range of photosynthetic bacteria:

- Phylum Cyanobacteria: contains both Photosystem I and II, using the Calvin cycle.

- Phylum Bacillota: only uses Photosystem I, without any associated synthetic cycle.

- Phylum Chloroflexota, order Chloroflexales, only uses Photosystem II, using the 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle.

The bacterial kingdom Pseudomonadati also contains a similar variety:

- Phylum Chlorobiota (green sulfur bacteria): contains Photosystem I, using the reverse Krebs cycle.

- Phylum Pseudomonadota (purple bacteria): contains Photosystem II, using the Calvin cycle.

Cyanobacteria became incorporated into eukaryotes as chloroplasts via endosymbiosis, allowing plants and algae to make use of photosynthesis, with both photosystems I and II.

Thermodynamics of photosynthesis

The biosphere, and life itself (such as a cell) is an open system, and one in a highly non-equilibrium state, using free energy to maximally generate entropy in the surroundings while maintaining a low-entropy internal state.

Intro-level explainer on the thermodynamics of life: here.

The concept of exergy is very helpful in understanding the thermodynamics of photosynthesis. The exergy content of an energy source is the maximum useful work that can be extracted reversibly from it. Although a plant radiates away as much energy as it receives (otherwise it would heat up!), the exergy of the incoming solar radiation is much higher than that of the outgoing thermal radiation, due to the Sun’s high blackbody spectrum temperature giving it a low entropy. The net exergy flux into the plant is what allows its internal processes to do useful work, which is to perform the endergonic, entropy-reducing reactions in photosynthesis, building up complex organic molecules from simple inorganic ones.

The transpiration stream of the plant provides the main high-entropy output of a plant in the form of water vapour, increasing the entropy of the surroundings significantly, allowing plants to harvest the external free energy of sunlight to create internal order. All life indirectly enjoys this benefit, since plants act as producers, providing energy (via metabolism) for organisms higher up the food chains.

In (Michaelian, 2012), it is shown that:

- The net entropy production rate of the Earth is much higher than all others planets (per unit surface area), attributed to the presence of life on Earth

- The surface layer of seawater produces 30 - 680% more entropy when cyanobacteria are present, compared to when they are absent.

Basic thermodynamic analysis of photosynthesis: here

Rigorous exergy analysis of photosynthesis: here

9. DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY

How is it that every cell in your body has the same DNA, yet different body parts can have completely different functions? How does your body know where to put everything? Development from an embryo is a tightly-regulated process, with the goal of controlling what genes get expressed where and when. There is a close relationship between evolutionary diversity and developmental diversity, and so we can study one to learn about the other. This is the basis of evolutionary developmental (evo-devo) biology.

Vestigial structures

Homeotic genes: Hox, ParaHox, Pax, MADS-box

10. POPULATION GENETICS

Phylogenetic reconstruction

Comparative genomics studies the similarities and differences between the genomes of different species. This can be used to reconstruct phylogenetic trees, which show how closely related different species are. The more similar two genomes are, the more closely related the two species are likely to be.

A test of the validity of this reconstruction can be done using a known phylogeny. In 1992, a study was done on an artificially mutated strain of the virus bacteriophage T7, whose genome was sequenced repeatedly as it reproduced in bacteria. The experiment was stopped after 9 different viral strains had emerged, and only their genomes were used in 5 different phylogenetic reconstruction algorithms. All 5 algorithms produced the same, correct known tree, out of the 135,135 possible tree structures, with slight variation in the time to branching, showing that the algorithms are valid and can be used to reconstruct phylogenies from extant genome data more generally.

Source: here

Great ape Y chromosome mutation rates

Sources: here

Statistical evidence of common ancestry among primates

Source: here (paper), here (video) and here (reddit post)

11. METAGENOMICS

Great ape gut microbiome

Analyses of strain-level bacterial diversity within hominid gut microbiomes revealed that clades of Bacteroidaceae and Bifidobacteriaceae have been maintained exclusively within host lineages across hundreds of thousands of host generations. Divergence times of these cospeciating gut bacteria are congruent with those of hominids, indicating that nuclear, mitochondrial, and gut bacterial genomes diversified in concert during hominid evolution. This study identifies human gut bacteria descended from ancient symbionts that speciated simultaneously with humans and the African apes.

Source: here

Adaptation of the CRISPR-Cas9 system

https://enviromicro-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01444.x

12. APPLICATIONS OF EVOLUTION

This section focusses on practical applications of the evolutionary theory, primarily in engineering, medicine and agriculture. It does not include applications of explaining aspects of biology itself, which are numerous. The utility of evolution serves as a ‘proof of concept’ that the theory aligns with reality.

Protein Engineering

We can develop entirely new enzymes using ‘directed evolution’ of proteins with a variety of uses. By artificially cloning the gene for an enzyme and introducing mutations, screening for activity and stability, we ‘artificially select’ more optimal enzymes for our use case. This is a well-established lab procedure that puts evolution into practice.

Glucose biosensors: when type 1 diabetics need to monitor their blood glucose levels to time insulin injections, they use a glucose biosensor, which typically works by measuring the rate of reaction of a glucose-binding enzyme. The wild-type enzymes found naturally are usually not stable enough for reliable operation in a biosensor (due to activity reduction on immobilisation, stability to temperature variations and cofactor dependence), so new enzymes are needed, which come from directed evolution. These are the most common type of commericalised glucose biosensors in use today. Although enzyme-free biosensors have been researched, they have not yet been commercialised due to lacking the chemoselectivity that enzymes excel at, so evolution-backed biosensors remain the state-of-the-art in type 1 diabetes management as of 2025. Source: here and

Lactate biosensors: another type of electrochemical biosensor making use of directed evolution. Lactate biosensors are used by high-performance athletes to monitor lactate levels in the blood and sweat, indicative of fatigue, and require directed evolution for thermostability. They are also used in hospitals at triage to test for septic shock or risk of meningitis. Source: here and here.

Artificial metalloenzymes: new enzymes can be designed to catalyse completely new chemical reactions unseen in biology. In one study (figure below), a new enzyme was evolved containing an abiotic di-rhodium cofactor, which catalyses the cyclopropanation of styrene and diazo compounds with enantioselectivity. Industrial applications include the synthesis of pharmaceutical (e.g. sulfonamide antibiotics), improvement of enzymatic biofuel cells, carbonic anhydrase-based carbon capture technology and bioremediation by degradation of toxins (PAHs, PCBs, organophosphates…). Source: here.

in the enzyme. Source: [here](https://www.nature.com/articles/nchem.2927).](/post/evolution-evidence/directed_evolution_hucca222e264223908c01fb941179ae07c_624275_e9387723610ac512bec29ffc5a10636b.webp)

Bio-detergents: subtilisin is a protease used in laundry detergents, which was engineered to be more stable at high temperatures and alkaline pH. Its cofactor dependence on calcium ions was also removed, as calcium would be chelated by EDTA in the wash. Source: here.

High-fructose corn syrup: glucose isomerase is an enzyme used in the production of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), which is sweeter than regular corn syrup. It was engineered to be more stable at high temperatures and to have a higher affinity for glucose. This allows for more efficient conversion of glucose to fructose, resulting in a sweeter product. Source: here.

Genetically engineered bacteria: E. coli can be engineered to produce new useful products, such as carotenoids. They can also produce bioplastics, which are biodegradable, although issues of scale-up and durability remain. Source: here.

Animal Model Selection

The animals used in lab studies for medicines are chosen based on evolutionary relatedness. They use rats for most in vivo studies since they’re one of the closest non-primate animal orders to us (order Rodentia). Rabbits are in another very close order (order Lagomorpha), and we are all mammals. For neurological studies, primates are sometimes used, as their brain structure is closer to ours, although animal welfare laws and ethics regulations mean these studies are only done for behavioural studies and occasionally for neurosurgery (e.g. neural prosthetic implants).

Without evolution, we’d be stabbing in the dark as to whether a particular animal would serve as a good model for our in vivo testing, which would mean significantly fewer successful drugs and therapies passing the animal testing phase.