The Inorganic Chemistry of Cisplatin

Exploring crystal field theory and ligand field theory through a famous chemotherapy drug

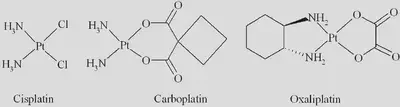

The platinum-based antineoplastic drugs are a class of anti-cancer agents with a surprisingly simple structure compared to most other pharmaceuticals. Unlike the majority of drugs, which are organic compounds, these drugs are coordination complexes of platinum. The most famous of these drugs is cisplatin, which has been used to treat a variety of cancers since the 1970s. In this post, we will explore the inorganic chemistry of cisplatin, focusing on the crystal field theory and ligand field theory that help explain its properties.

Stereoisomerism in Cisplatin

As seen in the above diagram, cisplatin (shown leftmost) is a square-planar complex. The two types of ligands, chloride (

Synthesis of Cisplatin: Exploiting the Kinetic Trans Effect

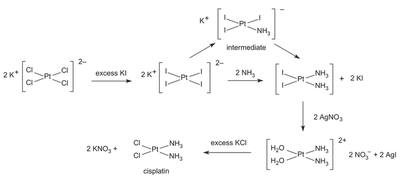

The scheme below shows the most common synthesis of cisplatin, starting from potassium tetrachloroplatinate(II) (

In the first step, an excess of iodide ions is added, undergoing ligand substitution to form the tetraiodoplatinate(II) complex.

In the second step, the stereoisomerism comes into play. Two equivalents of ammonia are added to the tetraiodoplatinate(II) complex. The first ammonia molecule replaces one of the iodide ligands. But when a second ammonia molecule approaches, it has two choices: it can either displace an adjacent iodide ligand, which would form the cis complex, or it can displace the diametrically opposite iodide ligand, which would form the trans complex.

Reaction kinetics turns out to favour one over the other. The kinetic trans effect is the phenomenon where the rate of ligand substitution is faster when substituting at the trans position to an existing ligand. The trans directing strength of ligands follows this series:

Considering the intermediate complex,

In the third step of the synthesis, aqueous silver nitrate precipitates out the iodide as silver iodide, leaving water molecules in the metal complex. Finally, in the fourth step, addition of a concentrated solution of chloride ions leads to another ligand substitution, displacing the water ligands and forming the final cisplatin complex.

Crystal Field Theory

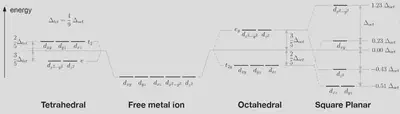

Crystal Field Theory (CFT) is a model that describes the bonding in coordination complexes. It assumes that the metal ion is a point charge, and that the ligands are also point charges. It can therefore be considered a model of ionic bonding. Depending on the geometry of the complex, the ligands will approach the metal ion’s five different

CFT is often successful in predicting some properties of complexes, such as the molecular geometry, the colour of the solution, and its response to a magnetic field. Let’s see how it can be done, using cisplatin as an example.

First, we will try to predict whether cisplatin will be tetrahedral or square planar, as both are possible for complexes with four ligands. We already know that the answer should be square planar from the first diagram, but this will be a nice test of CFT.

The electron configuration of neutral platinum atom is:

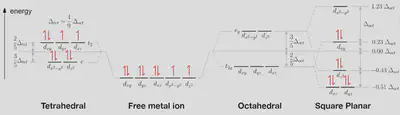

Next, we need to consider ‘strength’ of the ligands. This indicates the magnitude of the splitting that will occur. If the splitting energy is large, the repulsive effect of pairing two electrons in the same orbital with opposite spins will not be enough to overcome the energy difference, and the orbitals will be filled according to the Aufbau principle as usual. This is the strong field, low spin case. If the splitting energy is small, the electrons will pair up in the lower energy orbitals before filling the higher energy orbitals, leading to a weak field, high spin case.

Another series, the spectrochemical series, can be used to predict the strength of the ligands. The series is as follows:

According to the spectrochemical series, both chloride and ammonia are weak field ligands. This means that we can expect the splitting energy will be small, so the orbitals will be half-filled with unpaired electrons first, with the exception of the two highest energy orbitals in the square planar geometry, which are always separated by a large enough energy to make pairing up more favourable.

Our filled orbital diagram for the

We can now numerically determine the total energy of the

Predicting Molecular Geometry

For the tetrahedral case:

- 4 electrons (

- 4 electrons (

- 3 pairs of electrons in the same orbitals, giving an additional

Using the equation

For the square planar case:

- 4 electrons (

- 2 electrons (

- 2 electrons (

- 4 pairs of electrons in the same orbitals, giving an additional

The total energy for the square planar complex is then:

Comparing the two energies,

Since we already assumed that

The crystal field stabilisation energy (CFSE) is the energy difference between the given orbital energies and the original energy of the degenerate

We can therefore find

Since

Predicting Magnetic Behaviour

The two basic responses of matter to a magnet are paramagnetism and diamagnetism. Paramagnetic substances are attracted to a magnetic field, while diamagnetic substances are repelled by it. The magnetic behaviour of a complex can be predicted by the number of unpaired electrons in the

In the case of cisplatin, now that we know the electron configuration of the